What Stops L1 Cache from Being Larger?

Have you ever wondered why L1 cache sizes are relatively small compared to L2 and L3 caches? Actually, it has stopped being larger for a long time.

Let’s take a look at a modern CPU, the AMD Ryzen 7950X: (all the below CPU-Z images are from valid.x86.fr ↗)

And you might wonder: huh, this looks normal. L1 cache is 32 + 32KB per core, L2 is 1MB per core, and L3 is 64MB shared. This seems reasonable, with each level being larger than the previous one.

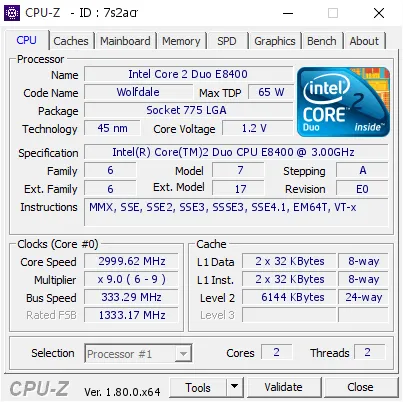

But what if I show you an older CPU, the Intel Core 2 Duo E8400 from 2008?

Surprisingly, it has the same L1 cache size: 32 + 32KB per core, L2 is 6MB shared, and there is no L3 cache. This means that for over 15 years, L1 cache sizes have not increased at all! Why is that?

We all want larger caches to reduce memory latency and improve performance. AMD even come with their 3D V-Cache technology to stack more cache on top of existing cache dies. So, what stops L1 cache from being larger?

This question emerged in my mind when I was learning CS:APP (Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective) about Virtual Memory System. As you can see here in the course slide, the modern CPU utilizes a “cute trick” for speeding up L1 cache access (credit: CS:APP3e Slide ↗):

TL;DR of the trick is that L1 cache is “Virtually Indexed, Physically Tagged”. It allows the processor to start looking for data in the L1 Cache before it has even finished translating the address from Virtual to Physical.

Normally, if CPU is built without this trick, accessing memory works in a strict sequence:

-

The CPU translates the Virtual Address (VA) to a Physical Address (PA) using the TLB.

-

The CPU uses the Physical Address to check the L1 Cache.

This is safe, but slow because step 2 cannot start until step 1 is finished. However, if we utilize the VIPT trick, the CPU can do two things simultaneously. By the time the L1 Cache has found the potential data row using the Index, the Address Translation finishes, and the hardware compares this physical tag against the tag stored in the cache slot we just looked up. Really smart!

But wait… For this trick to work, the bits required for the Cache Index (CI) plus the Cache Offset (CO) must fit inside the Page Offset. If the cache were larger, the CI bits would spill over into the VPN. If that happened, we couldn’t use the virtual bits to index the cache because that part of the address does change during translation.

Note that the cache size is calculated as:

where denotes the number of cache sets, denotes the block size, and Associativity is how many blocks are in each set. As Page Offset size is fixed by the system architecture (e.g., 12 bits for 4KB pages), this actually limits how large the L1 cache can be.

The standard way to cheat this limit is to increase Associativity. If we double the associativity, we can double the cache size without increasing CI. However, increasing associativity is not free. Remember that you want better performance (access speed) from L1 cache? Actually, the more associative a cache is, the longer it takes to look up data.

To select one entry from a cache, we need:

- comparators for an -way set associative cache, running in parallel. So 16-way associative cache needs 2x comparator power, and 2x area compared to 8-way.

- A multiplexer to select the right data output from the entries. But note: This mux or its control logic is often on the critical path for L1 hit latency. This mux consumes area and power, and more importantly, increases the access time.

- Hardware is physical. You need to consider about fan-out. The input address tag must be fanned-out to 16 locations instead of 8.

- You also need to deal with replacement policy! You need to track usage for 16 blocks instead of 8 to determine which one to evict. 16-way caches almost never use true LRU. They use approximations (Pseudo-LRU) or random replacement often.

- Once you have to physically stretch the cache across more of the core, the wire delays and clock tree load start dominating. This is one big reason designers would rather keep L1 small and very close to the pipelines.

- …

All these overheads add up. So back to our question: why L1 cache has not increased in size for 15 years? The answer is clear now: CPU designers have to make a trade-off between cache size and access speed. A 32 KB L1 is full of parallel tag comparators and big mux trees and hit on nearly every cycle, so it’s a power hotspot. Still, it is a very reasonable sweet spot for many modern CPUs, and its size has stayed flat mostly because other things scaled instead (L2/L3, prefetching, OoO machinery, etc.). Modern CPUs leaned into this idea:

- Keep L1 tiny but extremely fast.

- Grow L2/L3 aggressively for capacity and hit-rate.

- Use prefetchers, better branch prediction, bigger OoO windows, etc. to hide latency.

So instead of “make L1 bigger”, architects made the rest of the machine smarter. They bring things into L1 just in time with prefetch.

But wait, before you close this article, let me show you one more thing. I only show you part of the story. Let’s look at another CPUs:

It got 48KB L1 Data Cache and 64KB L1 Instruction Cache per performance core!

The Apple M5 CPU (I do not have the CPU-Z picture), is even more interesting: it has 192KB L1 Instruction Cache 🤯 and 128KB L1 Data Cache 🤯 per performance core! How? Well… let’s break them down.

Intel decided 32KB wasn’t enough for their Data Cache. But remember the VIPT Limit (Page Size = 4KB)? To get 48KB without breaking VIPT, Intel had to pay the “associativity tax” we discussed earlier. They made the L1 Data Cache 12-way set associative (instead of the common 8-way).

But what about Apple? Apple’s M-series chips have L1 caches that are 3x–6x larger than Intel or AMD. How???? Dude, there are no magic here.

-

Apple runs its CPUs at lower frequencies (~4.0 GHz) compared to AMD/Intel (~5.7 GHz and they are going even further!). Lower frequency makes it easier to access a large cache in 3 cycles.

-

Apple uses ARM, which has a fixed instruction length (mostly). This makes indexing and decoding slightly more predictable than x86’s variable-length chaos, allowing them to optimize large cache access differently.

-

Most importantly: While x86 is stuck with standard 4KB memory pages, Apple Silicon is optimized for 16KB pages. By using a 16KB page size, the ‘Page Offset’ becomes larger, effectively quadrupling the VIPT limit. This allows Apple to build massive L1 caches without needing complex hardware tricks or excessive associativity.

So what about AMD then? Would increasing L1 cache size to 48KB make Ryzen CPUs even more better than Intel? Well, it turns out that in their latest chip, the Ryzen 9 9950X, they increased the L1 Dcache to 48KB.

Is that the complete story? Not really. Remember we said “Apple uses ARM, which has a fixed instruction length (mostly). This makes indexing and decoding slightly more predictable than x86’s variable-length chaos”? So what about x86? Modern x86 instructions are complex and “ugly.” Before the CPU can execute them, it must decode them into simpler internal commands called “micro-ops.” It turns out that the Micro-op cache is a critical component in modern x86 CPUs.

Both Zen 4 and Zen 5 architectures feature an Op Cache, but Zen 5 has upgraded the design by utilizing two 6-wide Op Caches, as opposed to Zen 4’s single 9-wide Op Cache. The Op Cache is crucial because it stores pre-decoded micro-operations (uOps). When instructions are fetched repeatedly (such as in loops), the CPU can pull these uOps directly from the Op Cache instead of decoding the instructions again, which saves time and power.

The above text are from here ↗. Because this exists, the Icache doesn’t need to be huge; it just serves as a backup for the Op-Cache.

Hope you enjoyed this article! If you have any questions or something to correct, feel free to comment below.